I became a bionic woman on August 24, 2009, the day after my fifteenth birthday.

I’ve heard a lot of interesting things in bed before but “I like your scar” is rarely one. I never expected it from my college “friends with benefits” whose lips rested on the tip of where my scar starts and kissed all the way down my long, back-length scar.

“Yeah?” I questioned, feeling myself tense up.

“Yeah,” he replied between kisses. “It’s cool, like you bionic or something.”

Bionic. That does sound cool, but speaking from experience, it’s a long road to “cool.”

Scoliosis is a disorder that causes a sideways curvature of the spine and often occurs during childhood growth spurts.

They are as common as braces or a lazy eye — there’s one in every class. Unfortunately with my luck, while most kids' spines stayed slightly skewed, my spine continued to curve, and no amount of uncomfortable medieval back braces could fix it.

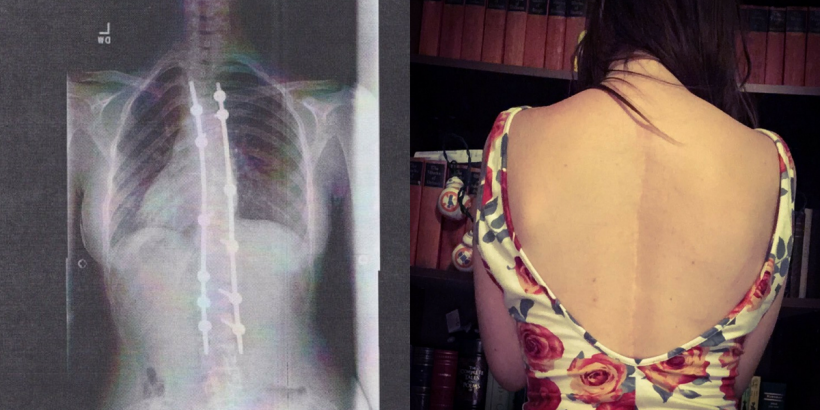

I became bionic on August 24, 2009, the day after my fifteenth birthday. It took a team of neurosurgeons, twelve screws, and two titanium rods to correct my 46-degree curvature in eight long hours. My orthopedic surgeon, my doctor for two years, was an interesting man. He carried around his silver tape recorder like it was another appendage. I almost did not recognize him without it. Nor did I recognize him four hours after surgery, half-conscious as he strutted into my room at the pediatric intensive care unit to show off the x-ray of me and my new hardware — like a proud parent with baby photos, declaring the operation one of his better successes.

I asked to see the x-ray and was handed a still curved spine but with harsh bright lines and dots, almost like steel cables. I thought it was a cool art piece until I remembered that it was me. It was my body, and those titanium rods and screws were inside of me.

“So, are like those like forever?” I asked.

“Yes. You might become paralyzed if we ever have to take them out.”

“Oh,” I said, handing him back the x-ray.

I proceeded to get violently ill. It turned out I was allergic to the medication in my I.V. drip, but I don’t think the news of my newly minted cyborg status helped any.

So I was a big success. Cool. But what did that mean for me?

Well, after being violently ill and hooked up to a million machines, it meant re-learning everything: sitting in a chair was a conscious task, turning my torso was limited. I relearned to walk at 10 p.m., half-naked and unwashed, in the hallway of the intensive care unit as Bongo, the St. Bernard therapy dog, dutifully followed me. The caring nursing staff cheered me on while I silently prayed to whatever deity was still taking my calls to have Bongo claw out everyone’s eyes, as they stared. Hospitals can bring out the best and worst in people.

When I could walk, sit, and hold down a meal, I could go home, but not without one more examination by my doctor who spoke his thoughts into his tape recorder.

“Patient (this man, who has been inside me has never actually called me by name), is being released from the hospital. Her deformity..."

“Wait; my deformity? I’m not still deformed anymore, right? Like, you fixed that?”

Wasn’t that the point of the surgery — to not only stop my spine from crashing into my lungs but to make me somewhat normal?

“Oh no, you’ll always be deformed,” he said, almost surprised that I was there before continuing to talk to the tape recorder.

Deformed, now that’s a loaded word.

I recalled Quasimodo with his one giant eye and the large hump. Was that me? Was that how people saw me? I thought of my mother who, during the entire month before the operation, forced me to bend over to “look at my hump.” This was supposed to fix me.

Yet I am still "deformed," held together by metal and bolts.

There is no handbook for the bionic. On the way out of the hospital, no one handed me a pamphlet called “So now you’re a cyborg.” I had to navigate my new spine alone without a guidebook. My initial recovery took six months of limited movement. I could not take the stairs for fear of falling. No sports, no hugging or touching; I couldn’t even bend over. I went to a tiny K-12 school — my graduating class was thirty-two kids, and the only thing worse than being a student in a small school was being different at that small school.

You Might Also Like: Feeling Body-Positive When You Have A Disability

Everyone knew about my surgery, and everyone had something to say:

“Does it hurt? Like can you still feel it?”

“Is that like plastic surgery? Like you didn’t need it done?”

“Yeah, you were kinda getting a hump.”

These comments and questions, much like my surgery, were invasive. I was trying to recover from major surgery already hyper-aware of my every movement; I didn’t need an audience.

On the top of my list of insecurities was the back-length scar I acquired from the surgery, making me both deformed and disfigured. I should have heeded the nurse's warning about not looking at my scar until at least six months, but curiosity got the better of me. Raw un-healed flesh, long red scar, healing bruises. A real Frankenstein creation.

Today I realize that it was my body still healing; it wouldn’t always look like that. But my first thought when I looked at myself — my new, altered body — was I’m a monster. I can close my eyes now and still see it.

Looking at your body in its worst state doesn’t leave you, it is its own scar.

It’s hard to pinpoint where a mental illness begins, but I’m pretty confident in saying that this was where my Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) started. I would spend hours in the mirror focusing on everything that wasn’t “right” — the unevenness of my shoulders, hips, and legs, and my hideous scar. My body didn’t seem right; I could feel the metal in me all the time. It felt unnatural and wrong. I couldn’t move past words like deformity and disfigured, becoming what I identified myself to be.

The final straw came on my first day back at gym class as I changed in the locker room. The girl next to me gasped as soon as I took my shirt off, “Ew, gross! What happened to your back?" confirming all of my worst fears.

I began to disassociate from my body, believing it was no longer mine. My only survival mechanism was to make myself numb to it — an empty shell.

My disassociating episodes were terrifying, and I knew I needed to make myself real again — to prove I still existed, even though deeply altered. I needed to look at it through a different lens. So I took a picture of my scar, six months after my operation. The results were not pretty, but after experimenting, I could use different filters to create something completely different. I cannot control my disability, or how my body moves now, but I can control how I view my body, and how I care for it.

I am more than my disorders. I am more than what happened to me.

My photo was in an art show, and someone asked me. “Is that you? What the hell happened?”

I replied: “Oh, I needed to develop some backbone, so I had some implanted.”

Dad jokes are the answer to everything.

It’s been almost ten years since my surgery, and body positivity is no easy feat, but every day I am learning. Yes, it is uncomfortable getting questions about my scar, whether I’m wearing a backless dress or in bed with someone new, but I’ve learned to accept this form I have taken.

I am unique, I’m different, and I’m bionic as hell.